Inspired Landscape Architecture

As Landscape Architects, we all bring a lot of ourselves into the design process.

We all have reference points in our mind from which we work. Some of these reference points are developed at University, but many are developed through life experience.

Below, I share with you some of the profound life experiences that have shaped my life and impacted on the way I see landscape. Through sharing this, I hope you will better understand how I think and the work I produce.

The ever-changing landscape

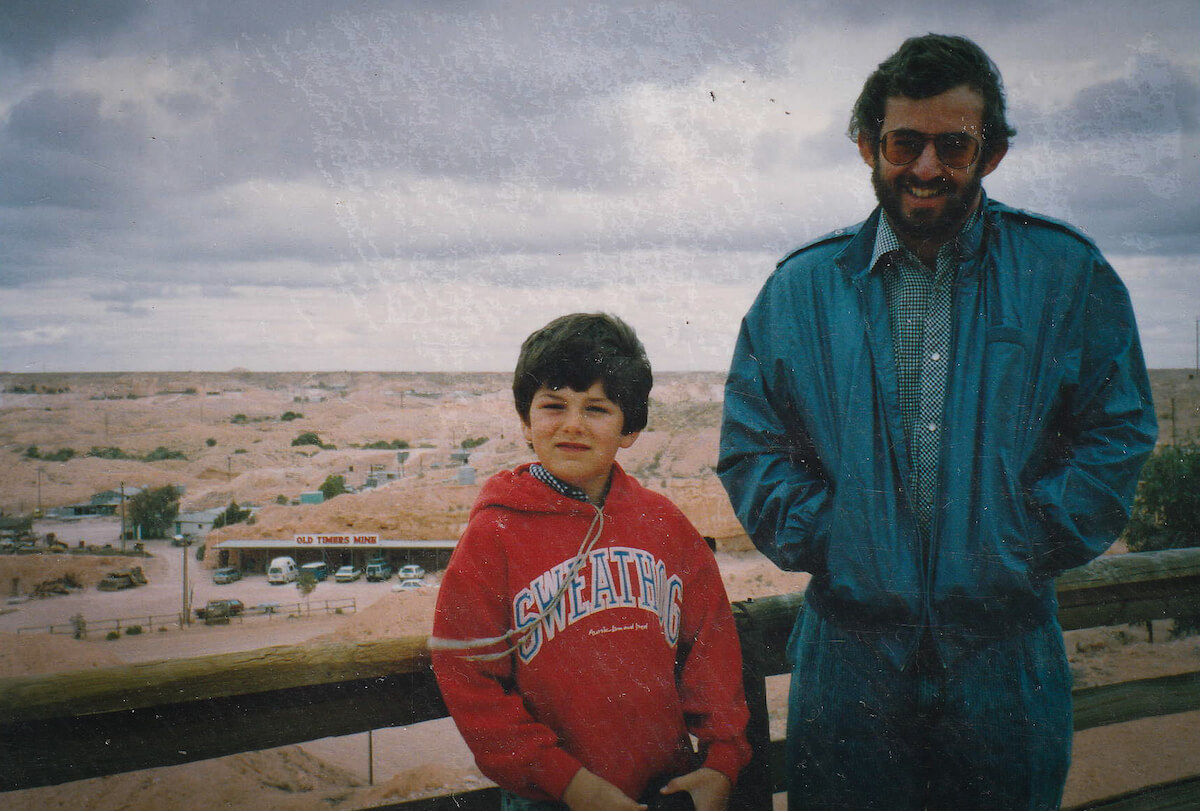

Growing up in Melbourne in the late 1980s, I was fortunate to be a member of family that travelled extensively around Australia. Every chance my parents had, we would pack the trailer and head off camping for weeks, sometimes months, at a time.

Looking back at it now, I think it is through these camping experiences that I first began to understand and appreciate the uniqueness of Place.

Over the years, the places that have stayed freshest in my memory have been the ones that embraced their local environment. From the design of the whole town to the details of the smallest spaces, the towns that integrated the surrounding natural landscape into the fabric of the town were the most memorable, and were the ones I most wanted to revisit.

Landscape gardening in Glen Iris

Growing up, I was also lucky to come from a family of prolific gardeners and my first job as a kid was as garden pruner at my grand-parents house in Glen Iris. With their careful guidance, I developed an appreciation for trees, shrubs, plants and a love of being active in the garden.

The meditation garden

In my mid teenage years, I went through a health crisis that made me reassess the importance of almost everything. It was one of my life’s pivotal experiences and one that lead to a set of unique understandings. At 15, I was diagnosed with a significant neurological disorder. At the time, I was one of the youngest people in Victoria to have the condition. I still remember being in Royal Melbourne Hospital and my family members visiting me with tears in their eyes, and the groups of doctors visiting my bed to discuss my condition, but I never cried or felt self pity. It was unavailable to me. Not until many years later could I cry or express emotions about what had happened.

In the years that followed, my mother researched tirelessly and with her guidance we explored alternative and complementary methods of healing. We followed the teachings of Ian Gawler, Anvi Sali and Bob Sharples. I turned my gaze inward and became very proficient with mindfulness based meditation practicing for up to an hour a day.

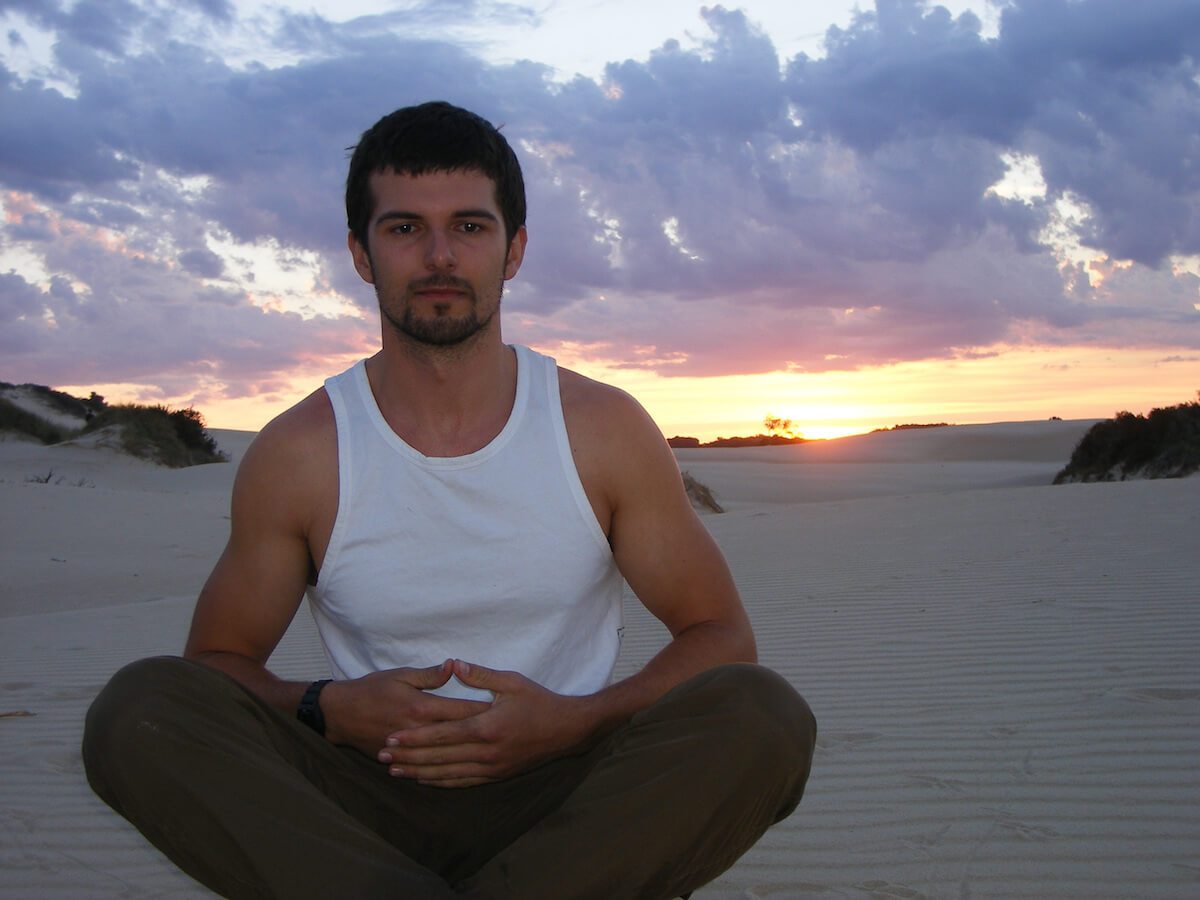

While the rest of my friends worked hard to finish high school, I worked hard to recover my health. Meditation expanded not only my connection to the present moment but also increased my sensitivity to my surroundings. I found I could not effectively meditate in disconnected spaces and the quality of my meditation was closely linked to the environments in which I meditated. For me, it had to be a living, organic space. I found living, natural spaces so engaging that they became precursors to a quiet, observant mind. So much so that I began to think about creating them.

It helped if I could feel the wind on my face, the sun on my skin and the earth under my feet. A place where I meditated well was one where I felt connected to nature yet feel hidden, translucent and invisible. Secret Creek By 1999, I was in a position where my friends were finishing year 12 and thinking about the rest of their life, moving on to university and travel, whereas I thought about how happy I would be if I could get just through to 30. I had a goal; 30.

Healing Gardens to Healing Landscapes

In the 3 years from age 15 to 18 my condition stabilised and I had turned my focus to becoming fit, healthy and living for the moment. I became stronger, leaner and faster than all my friends. I had taken up trail running and had transitioned my mindfulness practice from seated meditation to running.

With every footstep, I would focus on feeling the energy exchange between myself and the surrounding trees. As I ran, I visualised the trees healing me and I them. When my mind was clear, I would glide as I ran my lungs full of air. When my mind was clear I never puffed.

This experience seemed most available when I ran on unmade earthen tracks below trees. In later years, I was really upset when the council decided to formalize the pathways in a park I ran in, but I was too embarrassed to mention why I didn’t like the idea of made paths.

During these years, I developed a keen interest in alpine skiing. Skiing brought me close to environments where I felt the most connected. My first trip to the snow was a school camp in year 9. When my parents saw the bliss that skiing brought me, they supported me to ski as often as I could, and with a few pointers from my Aunty Sue I taught myself to ski.

By age 19, with my health fairly well managed I became an Alpine ski instructor at Mt Buller. In the years to come I would follow winter around the world (Mt Buller, Thredbo, Park City UT, Crested Butte CO, Whistler BC) living season to season. Through this time, my love of mountains and rocky alpine environments deepened. Tippity St Cricket Ground Standing on top of a mountain on a sunny day with skis on my feet, my mind was completely clear, my focus entirely present and I was free.

Active Landscapes

After 7 ski seasons I returned to Melbourne to rejoin the city. After having followed the snow it was really hard to return and follow the patterns of existence the city dictates.

By this point I felt confident enough in my health to give the city a go. I had begun to miss my family and crave meaningful human connections instead of season to season friendships. My interests had further developed, and I was venturing away from ski resorts towards telemark ski touring, multiday bushwalking and martial arts.

In my last season in the snow, I was beginning to enjoy ‘cross training’ more than skiing. It was time to move on and head home

In my last two seasons in Canada, I cross-trained for skiing by taking up Siberian Sandboxing, which at the time was making the transition from being a competitive kick boxing gym to being a fitness and conditioning gym. The program was run by Sasha, a former Russian navy seal who had escaped to Canada many years earlier. Sasha was someone I didn’t really know but respected; I liked the way he approached life and his dedication and self motivation. Having been in a ski instructor’s role for a number of years, and with Sasha as my inspiration, I returned to Melbourne and became a personal trainer and condition coach. As always, I favored outdoor training where engagement with the natural world was at its fullest. I chose locations for training sessions where my clients had the opportunity to connect meaningfully with the natural environment. I ran a successful personal training business for a few years before I found that I was became disillusioned with the Industry and the culture that prevailed. The industry was beginning to shape me rather than me it.

As a fitness trainer, I opted for strength and conditioning training and was one of the first certified kettlebell instructors in Melbourne

Having been significantly unwell, my motivations to be fit had always been very close to my existence. One day in the gym a memory of Sasha came to me. It was a story he had told about how in Russia there were no mirrors in the gym. I looked around at where I was and begun considering my next attempt at rejoining the city.

A shared love of Landscape

I had a plan to go back to Canada and to the ski industry if it didn’t work out it in the city. By the time I had finished with the fitness industry and ready return to Canada, I had met Serina. In my travels, I met lots of amazing people, but none that I felt really understood me. Serina did and we shared a wonderful energy. She was my girl and before I knew it we had bought a house together: an old, rundown Californian Bungalow in Preston, Melbourne.

Together we began imagining what we could do with it. Serina was a wonderful designer in her own right. She felt the colour others see. We put together designs for renovations, extensions and gardens. Over holiday breaks we bush walked, sometimes for up to 10 days at a time. In the wilds of the Tasmanian backcountry was where we felt most at home. Most free.

Naturalistic Landscape Architecture

On our hiking trips we met a wide variety of people, many of whom were inspiring in their own way. Some of the most memorable being German lone wanderers, an architect surviving with a fry pan with fishing rod, and two surfers who had hiked 40km with boards and were spear fishing to survive. We shared a meal of fish with them eating off their surfboards.

Through our bush walks we wondered why gardens in the city couldn’t be as evocative as the wilderness we had experienced, and bring some of the splendor of the backcountry back into daily life. Smith Creek

Landscape Architecture in Banyule

The design work I had produced for our house in Preston became a folio that got me into RMIT. Completing the 5 years of full time study developed me significantly as a designer and a person and it provided me a lot of stimulation for how I might think about practicing Landscape Architecture.

Having had the experience of being somewhat consumed by the fitness industry, I entered the Landscape Architecture profession very careful about not allowing something I was passionate about to be drummed into something unpalatable. Not again. I realised even before I had graduated from university that I needed a more hands on connection with the work I produced than most Landscape Architects have. My lecturers seemed to often say Landscape Architects don’t build, they just design.

My logic was always that if a design is essentially a plan for an end result it would be crazy if the visionary behind the design wasn’t associated with the designs production. The last layer of design happens on site as the drawing is interpreted into form. The gap between the designer and the builder seemed foreign to me. Maybe I was in the wrong profession? But I loved Landscape Architecture, Urban design and the complexity of thought behind the work that these schools of thought produce.

I was stuck somewhere between professions.

I found the reassurance I needed to continue when I researched the methods of grand masters of the profession. Design position Seeing some of their methodologies kept my dream of becoming a Landscape Architect alive.

By the time I graduated I knew that I was going to have to be different. Rather than fitting into the profession I was going to have to make the profession fit into me.

Sharing the passion of Landscape Architecture

By the time I graduated, Serina was 6 months pregnant with our son Beau and I had a long list of landscape projects waiting for me. Really amazing jobs that don’t come up often had cued themselves up through connections from friends and family. This was a once in a lifetime opportunity that I decided I could not let pass to hone my skill and to deepen my knowledge. Windowscape. I always felt that if I didn’t pick up ‘the tools’ for a period of time I would never truly understand the work I would be producing in the office. So I set about finding out what can be done with local plants and materials.

To this point I have designed and constructed gardens that bring a sense of peacefulness, wildness and place to the home landscape. California Dreaming

With each garden that I have worked on I have strived to bring a sense of the local context into the design. Gardens need to ground the people they are created for and to give them a connectedness to the places they inhabit. This is a need identified through civilizations and human history.

Becoming a Landscape Architect has lead me on a journey of continual learning, which continues to this very day. It seems the more I learn the more there is to learn. There is so much knowledge out there in the community and when you share with others they share with you.

It is important to me to work with people who share my passion for landscape. Working with you Today, this journey continues and I am very grateful for the opportunity to share something with others that I am so closely connected to; landscape.

You must be logged in to post a comment.